Touristification and urban division in Samarkand, Uzbekistan

In 2024, I visited Uzbekistan, becoming myself part of the new wave of tourism that has intensified in the country in the recent years. As often happens in such processes, international recognition did not only certify the importance of these sites: it triggered material and political transformations, accelerating restoration projects, infrastructural investments, and the construction of an appealing touristic image designed to circulate within the global cultural marketplace.

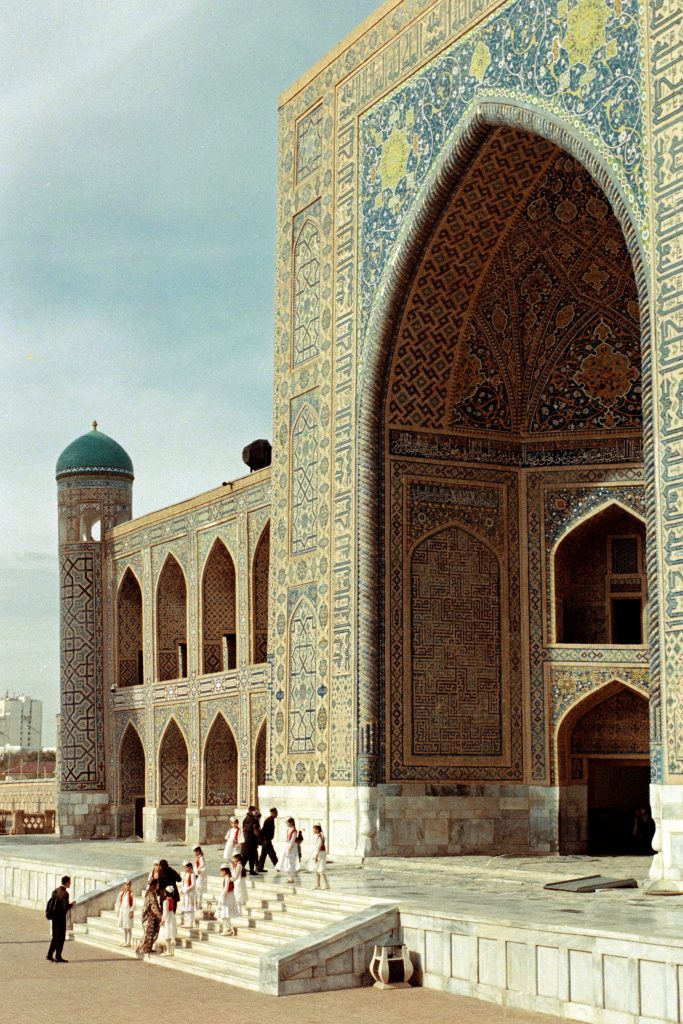

From Tashkent to Bukhara and Khiva, and finally to the emblematic Samarkand, an extensive restoration program has brought form and color back to madrasas, mausoleums, minarets, and entire architectural complexes that would otherwise have been lost. Archival photographs displayed throughout the city reveal the state of decay in which most monuments once stood, bearing witness to the extraordinary efforts undertaken to recover and breathe new life into an immense architectural heritage.

In Samarkand, however, this “rebirth” has not been merely aesthetic: it has become the driving force behind a profound reconfiguration of urban hierarchies, with consequences that extend far beyond heritage conservation and deeply affect the everyday lives of residents.

It is precisely in this city that a complex process becomes visible: the reorganization of the central urban space for the almost exclusive benefit of tourism, with all that this entails in terms of forced relocations, demolitions, and the creation of a nearly dual city: one half proudly displayed and meticulously polished, the other actively concealed and excluded from the project of recovering national cultural memory.

The orientalist image of Samarkand and its reconstruction

The Western imagination of the Silk Road is highly specific: perfectly symmetrical madrasas, turquoise domes, bazaars, carpets, and golden light. An East crystallized into an image that, one might say, we have constructed for ourselves over the centuries. This narrative, however, is not always harmless. More often than not, the Orientalism projected onto “distant” places and figures produces images that become more “real” than reality itself (see Edward Said), images to which countries frequently end up conforming, especially when their economies depend on heritage valorization and predominantly foreign tourism.

Samarkand has been no exception.

Many of the sites we now consider “ancient” are in fact modern reconstructions, the result of massive restoration campaigns initiated during the Soviet period after earthquakes and decades of neglect. Until around fifty years ago, many madrasas survived only as precarious skeletons. Soviet intervention quite literally recreated the very image of Samarkand that we consume today.

Restoration preserved essential monuments, but it also contributed to the construction of a specific representation of heritage: coherent, polished, photogenic, and aligned with external expectations, sometimes almost excessive, if one considers the colored light displays that illuminate the madrasas of the Registan every evening at 9 p.m.

And, as often happens when heritage becomes spectacle, new tensions, contradictions, and power relations emerge concerning who is allowed to live in, inhabit, and make use of historic city centers.

The urban transformation of Samarkand: a canalized city

One of the most significant effects of Samarkand’s touristification has been the redesign of the entire city center with a very clear purpose: to create a linear and unambiguous route along which visitors can encounter all sites deemed “touristic.”

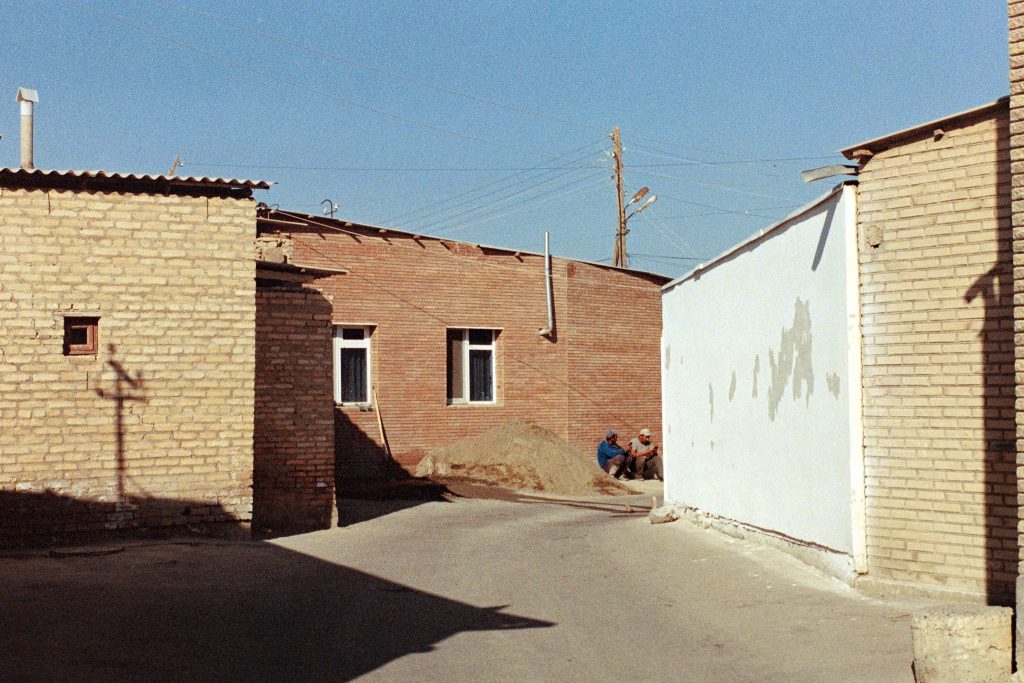

This kind of planning, however, has come at a very high social cost: residential neighborhoods demolished and rebuilt from scratch, families relocated, and physical barriers erected to conceal the vibrant yet less aestheticized parts of the city.

Along Samarkand’s main central avenue, tall metal walls now stand, painted and integrated into the visual landscape so as to be almost imperceptible. These barriers are designed to blend in with the colors of the recently restored facades of the city center. Had I not known of their existence, and had I not stayed in a guesthouse behind them, I likely would never have noticed them. Approximately every fifty meters, nearly invisible doors provide access to the mahalla, the historic residential neighborhoods that are still inhabited. The doors are open during the day and closed at night, yet remain accessible at all times.

Beyond these barriers extends a different city, shaped by shared urban spaces: local mosques, small shops, gardens, squares, and courtyards.

The mahalla: Samarkand seen from a different perspective

During my visit to Samarkand, I stayed in a guesthouse outside the historic center. Upon arriving in the city, I crossed one of the many open doors embedded in the dividing metal walls that connect the mahalla to the rest of the urban fabric. My guesthouse was nestled within a dense network of narrow alleys and closely packed buildings: spaces markedly different from the wide boulevards and monumental, elaborately decorated madrasas that characterize the rest of the city.

Although institutional care for public space in these neighborhoods is visibly different from that of the restored central areas, the mahalla today host ordinary forms of urban life and, above all, a remarkable degree of cultural diversity. These neighborhoods are primarily home to Tajik, Jewish, and Lyuli communities. The partly unpaved streets form a labyrinth of buildings with exposed pipes and aging gates. Life unfolds in the streets as well, among small local businesses, places of worship, and everyday gathering spaces. Mosques are numerous and of particular beauty; many have been recently restored, and the intricate decorations of Uzbek arabesques gleam in hidden corners of the neighborhoods, places one quite literally stumbles upon by chance.

What I encountered, therefore, was neither a better nor a worse version of the city, nor a more authentic one compared to the newly curated vision presented to the public. Rather, the mahalla concentrate a form of life that is historically and structurally different, and that does not align with our exoticized ideal of Samarkand, an ideal that certainly exists, but within clearly delineated boundaries.